Thus far, Alston's Dodgers, leading the National League by a dozen games, have looked like champions most of the time. Last week Alston himself, a 43-year-old, long-legged ex-schoolteacher, looked comfortably at home sitting behind his desk in his white and royal-blue Dodger uniform No. 24. On the shiny red outer door leading to his office in the clubhouse at Ebbets Field there is no name plate. Only the word "Manager" is printed there, emphasizing the expendable nature of such jobs.

'When I came here,' Alston said, 'nobody had heard of me, I guess, except in Montreal and St. Paul, but many of these guys had played for me before in the Brooklyn farms. I had always gotten along with them and I didn't anticipate any trouble with anybody.'

'No, I wasn't scared when I got the job. When you've been in baseball as long as I have, well, it's just another game. Things are so much the same in AAA clubs and here. Here you have more fans and the pressure's a little more and there's more at stake but, after all, it's the same baseball game, wherever you play it.'

Alston, who taught science, biology and industrial arts and coached basketball as well, meted out learning and discipline with equal authority during his scholastic years. Once he spanked a seventh-grade student for 'fooling around the water cooler.'

'But you can't get away with that in the East,' Alston grinned. Instead he imposes fines, suspensions or warnings to bring his class of major leaguers to order.

'To be a good manager you have to have good players," Alston said. "That's 100%, and I'm lucky. Very much so. This club is pretty much professionals who conduct themselves on and off the field as pros, and they don't get much discipline in that regard. I would like to treat everybody fair and square and equal with no pets or favoritism to anyone, and yet in order to get the best out of them, you may have to kick one in the pants or pat the other on the back, and if that's being fair, O.K. You try to treat everybody the same, but you've got to do it a little different way.'

Next door to Alston's office, in the locker rooms, the Dodgers were suiting up for the game.

'We have plenty of time to talk,' Alston said, 'they'll ring a five-minutes warning bell.' He lit a cigarette and settled back in his swivel chair.

'This year somebody said I was changed, but in my own mind that isn't true. I don't think I've managed any different. The big difference in the club standing is easy to see, that Newcombe is pitching very good, like he did before he went into the service. He's had no sore arm. Campanella's hand was certainly all right and he's hitting a lot better, and we got a lot of help from Roebuck in relief. In fact the whole pitching staff has been better.'

'Robinson is in better condition than last year. At least he's not bothered with injuries. His weight is down and he's been a big help to us. Jackie is very good on the bases. He knows his baseball very well. The thing that happened in the spring, of course, got into the papers, and by the time it got around two or three times it was a lot bigger than it actually was. Jackie and I got our differences settled in one day and we were all ready to go to work again. Jack certainly wants to win. Although he's lost some of his speed, he has one of the best reflexes in running, bunting and making plays. His reactions on the bases and his quick starts and stops make him still one of the best base runners we got.'

'When we win a ball game," Alston continued, 'we come in here and we're just as happy as hell. One day it's Snider or Hodges or Newcombe or whoever it is-the club wants to win and where the credit goes doesn't matter.'

'Certainly it doesn't to me. I think it takes support from all 25 of them, clear down to the 25th man.'

'When I went home to Darrtown [Ohio] last winter,' he continued, 'I studied about the ball club and looked over the records and thought about what could be done this year. I think about it as much as anybody, I suppose, but I don't go to the place where I don't enjoy myself off season. My dad, he lives just across the street. He's part-time retired. He works in the summer when I'm playing ball and in the winter he takes the time off.'

'Three years ago we built our house. My dad laid all the bricks and mixed the mortar. He's pretty neat with his work. It probably took him a little longer than some of 'em, but he did a smash job. Last winter we did some hunting and we played around in the carpentry shop in our basement. In fact we made an extra room there, all pine-paneled, and that took my mind off baseball.'

'After dinner, dad would come over and we'd play a couple of games of pool. I built a billiard room. We'd watch the fights on TV and play cards - pitch. We play bridge too. Dad and I against my mother-in-law and my mother. That's quite a battle," he grinned. 'We get into a few arguments, but nothing serious.'

This coming winter Alston will have additional bridge hands in the house. His only child, Doris, 22, and her husband, Harry Ogle, a former Air Force sergeant, along with their blond, bat-swinging 2-year-old son, Robin Dean, will live with the Alstons while Ogle resumes his schooling at the University of Miami in Ohio, his father-in-law's alma mater.

'My home life is pretty pleasant,' Alston said. 'It's what I'm used to, and I couldn't get out of character if I tried. It kind of depends upon how you've been brought up and how you are. Why, I can stand in my back door and shoot chicken hawks off the fence.'

'Darrtown has only 156 people. You got plenty of parking space there. When I start home and get within half a block of my house, I can just turn the switch off and let it coast. Wherever the car stops, that's all right.'

'We got a grocery store, a filling station, a garage and a Hitching Post. The Hitching Post is a little bar. The fellow who owns it is a good guy and every Christmas he puts on a party for all the kids. Last year there were about 1,200 there. They sure all don't come from Darrtown 'cause we've got only 156 people.'

'As far back as I can remember I wanted to play ball. That was the big thing. We lived on a farm near Morning Sun, Ohio, and there was nobody to play with, neighbors or anything. When the old man wasn't out there to play catch with me, I was bouncing the ball around on the barn door. That's how I got my nickname, Smokey, 'cause I used to have a real fast fireball.'

'We moved to Darrtown when I was in the seventh or eighth grade. I sold my pony and bought a bicycle. In Darrtown, there was a big vacant lot, sort of a commons. Some man kept it real nice and grassy and green, and we'd play ball there. My dad was interested in ball and he supplied the balls and bats for us. I'd get the kids together-I wouldn't want to say I ran the thing - but in order to get to play ball, I'd gather up a few kids. If you want it you have to organize it, all right. I think that went on in high school when I was captain of the baseball and basketball teams and also in college. Organizing things came sort of natural and easy to me. I was a pitcher, but when I started college they wouldn't let the pitchers do much hitting in batting practice. I liked to hit, so I became a shortstop.'

Before he went to college Alston married his high school sweetheart, Lela Alexander. They lived first with her folks and then his, but to finance his education he drove a laundry truck, worked in the school cafeteria and racked balls in a pool hall. After graduation he played professional ball in the summer and taught school and coached basketball in the winter.

'When you're in the minors you don't make much money, and teaching isn't the most profitable thing in the world,' he said mildly, 'but between the two we did all right. The only thing is, it overlapped. Whenever I took a teaching job I told the superintendent I was playing pro ball and wanted it understood I was going to leave when the ball season opened. They had to get a substitute for me every spring, and they got tired of that. To be blunt about it, they fired me.'

'You have to choose between baseball and school,' they said.

'I said, 'Well, if you put it like that, there's no doubt in my mind, it's going to be baseball.' '

Three years ago, he retired from teaching.

'I suppose the darkest part of my career was when I first began to realize I wasn't going to make it as a player,' Alston said. 'I played AAA ball a few years, and that's about it. I had enough power, but I couldn't hit often enough, which is the trouble with a lot of fellows. I was never any speed merchant, either. I hit over .300 most of the time in the minor leagues, but I couldn't hit the good pitching, just the mediocre pitching.'

Even the memory of this failure, reflected in his sensitive face, saddened Alston. But after a moment he went on.

'In 1936, the Cardinals bought me at the end of the season. There was a month to go, and except for one time at bat when I struck out I sat on the bench. I had only sat on the bench twice in the minor leagues. It's tough sitting on the bench.'

His voice trailed off. He knew how his own rookies felt sitting on the sidelines, itching to play, to hit the home run that wins the game and the glory.

'Up until I went back to the minors I didn't give much thought to managing. A player, especially a young player, doesn't think too much about how he would manage or what he would do in certain situations. He just takes the orders and bunts when he's supposed to and does what the manager says.'

In the fall of 1953, when Walter O'Malley, president of the Dodgers, was looking for a manager to replace Charley Dressen, Walter Alston, who had been on the Dodgers' farm payroll for eight summers, never applied for the job.

'I knew he knew what I could do,' Alston said quietly. 'If he wanted me, he'd come and get me.'

There was joy in Darrtown that November night when Alston's appointment was announced. He flew to New York to meet the press and make it official and when he returned home the townsfolk turned out with welcoming signs and picnic baskets.

'It was a real nice party,' Alston said with a shy smile.

His reception in Brooklyn was less cordial. The press, accustomed to the pyrotechnics of Leo Durocher and Charley Dressen, was baffled by Alston's seeming mildness.

'Well, I'm going to be just the way I am and I'm not going to put on any fancy stuff just to impress people,' Alston said, recalling that trying period. 'I could go out there and raise hell with the umpire and jump up and down, but I don't think I will. I want it so that when I do go out there I've got a legitimate reason, and it'll do more good that way.'

'I'm not superstitious, but you just don't do anything to change the luck. When your line-up is hitting pretty much like ours, you say, 'Well, we'll go pretty much the same as we did last night.' As long as everybody's hitting and you're winning your share of the games, you don't have to worry about switching around very much. Your main problem is you set up your pitching and keep them in rotation and give the guys who need it an extra day's rest, and pitch them against the club you want them to pitch against. For instance, Russ Meyer has always gone good against the Cubs. We try to work it so Meyer'll pitch against the Cubs and probably Erskine against Milwaukee.'

'When you're on the defensive, you're worrying about your line-up and who you have coming up next, whether they're right-or left-handed batters, and if your pitcher gets in trouble, whether you have a good pitcher in the bull pen. Sometimes you want a right-hander and a left-hander warming up-if you've got a lefthander available. We don't have many left-handers. You may want Roebuck and Hughes to be warming up, although they're both right-handers. There are certain hitters I would rather have Hughes pitch to than Roebuck and vice versa.'

'When you're on the offensive of course, the score determines the whole thing, but you're thinking about your own line-up and who you have coming up. If the first man gets on, do you want to bunt or hit and run? You've got to think about those things in advance. If you're behind in a ball game, you know you want to use a pinch hitter for your pitcher and you have to be thinking about the bull pen again, who you're going to put in and then give him enough time to warm up.'

'We're out in front now,' Alston said cautiously. 'I think that being with baseball as long as I have been, you know that over 154 games you're going to have some good streaks and some bad streaks and you know that anything can happen. We can turn around and have some bad luck and some injuries that would hurt us. It could keep us from winning the pennant, but if everything goes all right we have a better chance than anybody else.'

The warning bell sounded in the clubhouse. There were five minutes to go before Alston had to join his players.

'I think I learned my lesson in St. Paul," he said as he rose from his desk and went over to the locker in the corner and started to put on his spikes. 'One year we had a six-game lead and nine games to play and we end up winning the pennant by one half game and we had to win a double-header the last day of the season to do it.'

He allowed himself a hopeful smile and a prediction. 'We've certainly got the percentage on our side. Brooklyn has been in several World Series and never won one-but we have to win the pennant first.'

Tightening the laces in his shoes, he said, 'Right now I'm worrying about tonight's game.' He stood up to his full six feet two inches, adjusted the visor of his cap and started toward the field.' "

Biography - Walter Emmons "Smokey" Alston

PRO CAREER

"DARRTOWN BOY REPORTS TO ST. LOUIS CARDINALS

Smokey Alston Gets Chance in Big Time Show

Butler county will claim another big league baseball player September 7, when Walter “Smokey” Alston, of Darrtown, will report to the St. Louis Cardinals, who are in the thick of the National League pennant fight.

Alston, who starred at shortstop for Miami University nines for three years, broke into professional baseball last season, following his graduation. Playing with Huntington, West Va., in the Mid-Atlantic League, Alston owns a batting average of .333 and is leading the loop in home runs. He plays first base for Huntington, having been shifted to that position soon after he joined the team.

Local fans who have seen “Smokey” in action say that he should fit in perfectly with the famous Gas House Gang. He was always noted for his aggressive style of play and should feel at home with the Cardinals.

Alston will have his work cut out for him to equal the feats of two other Butler county diamond stars who made good in the majors, Cal Weilenmann of Hamilton, and Charlie Root of Middletown. Both Weilenmann and Root were pitchers and if Alston can make the grade, he will be the first local product to be in action every day in the major leagues. Harry Wilke, Hamilton boy, was a member of the Chicago Cubs several years ago, but did not play regularly."

LEFT: This undated Hamilton (Ohio) Journal News article was found among the scrapbooks maintained by Mrs. Albert (Bernice Weiss) Lindley.

Minor league level:

During his minor league playing career, Walter Alston led the Middle Atlantic League in Home Runs (four times), Runs Batted In (twice), and Runs Scored (once). Alston's seasonal highlights, in the minor leagues, included:

1936: 35 home runs.

1940: 28 home runs (this was his first season as a player manager).

1941: 25 home runs,102 runs batted in, and 88 runs scored.

1942: 12 home runs and 90 runs batted in.

Major league level:

In 1936, Walter Alston was a first baseman for the St. Louis Cardinals. He appeared in one major league game, as a substitute for the future Hall of Famer, Johnny Mize.

MANAGING CAREER - minor leagues

Webmaster note:

Wikipedia reports that the Portsmouth Red Birds were a minor league baseball club, located in Portsmouth, Ohio. The team played in the Middle Atlantic League between 1936 and 1940. During the club's first two seasons, it was known as the Portsmouth Pirates, as a Class-C affiliate of the Pittsburgh Pirates. In 1937 the team became affiliated with the St. Louis Cardinals and were then renamed the Portsmouth Red Birds.

The following is taken from thebaseballpage.com

"In 1940, Alston's fortunes changed forever when he was offered the chance to play and manage at Portsmouth in the Mid-Atlantic League. That year he led the loop with 28 homers, but the team could only manage a sixth place finish. The next two seasons, in 1941 and 1942, serving as player/manager, Alston led the Mid-Atlantic homers and RBI both years, earning a promotion to Rochester, where he surrendered his managerial cap and performed as a player only. In 1944, the Cardinals released Alston, but Branch Rickey, formerly the Cardinals GM and now the president of Brooklyn Dodgers, hired Alston to play and manage in the Dodgers' system. With the Dodgers, Alston guided St. Paul to the Junior World Series championship in 1949, and the next year found him in Montreal, Brooklyn's top farm club.

The quiet, unflappable Alston spent four seasons in Montreal, grooming several Brooklyn stars for the big club. When the Dodgers' managerial position was open after the '53 campaign, O'Malley surprised the press and fans by hiring Alston, who was not highly regarded by most experts outside of the Brooklyn system."

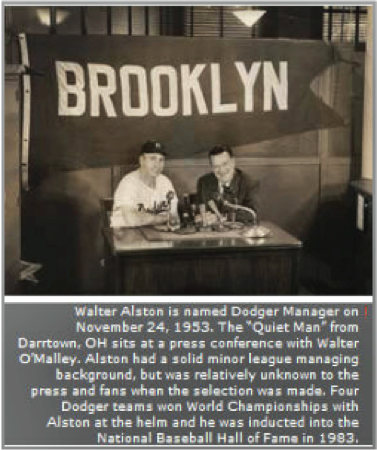

Walter Alston was named manager of the Brooklyn Dodgers in November 1953.

In his second year as the Dodgers manager (1955), Walter Alston led Brooklyn to the National League pennant and the team’s first World Championship. The team repeated as National League Champions in 1956.

During his 23 years as the Dodgers manager, Walter Alston won seven National League pennants: two as the manager of the Brooklyn Dodgers (1955 and 1956) and five as the manager of the Los Angles Dodgers (1959, 1963, 1965, 1966, and 1974.) Walter Alston led the Dodgers to four World Series Championships; one in Brooklyn (1955) and three in Los Angles (1959, 1963, and 1965).

Walter Alston was named National League Manager six times. He guided the National League All-Stars to victory seven times.

He amassed 2,042 wins, before retiring after the 1976 season.

Walter Alston was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1983.

Webmaster Note:

Tracking Walter's trek to the top

I remember that, as a youngster, in the late 1940s and early 1950s, after listening to stories that my father told me about attending high school with Walter Alston back in the mid-30s, I diligently read the minor league baseball standings in the local newspaper, so that I could stay informed about the progress of "Smokey" and his teams in St. Paul and Montreal.

During his seasons at Montreal (in the AAA league), I read about many of Walter's players moving up to the "big show" - with the National League Brooklyn Dodgers - while "Smokey" continued to toil, in the minors.

Then, in the fall of 1953, the unbelievable happened...Walter O'Malley, general manager of the Brooklyn Dodgers announced that he had decided to appoint Smokey to manage the MAJOR league Brooklyn Dodgers! See more about Alston's signing in the following section that is titled "Dodgers Sign Who?"

The Dodgers won their first World Series in Walter's second season and the man from Cherry Street in Darrtown went on to manage the baseball Dodgers for 23 consecutive seasons.

As successful as he was at the big league level, it seems appropriate to note that Alston earned his major league opportunity by honing his managerial skills for 13 seasons of relative obscurity at the minor league level.

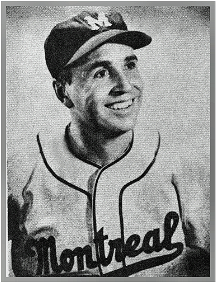

According to baseballreference.com, Alston began his managerial career in 1940, as a player-manager for the Portsmouth (Ohio) Red Birds, in the class C Mid-Atlantic league. For the next two seasons, he held the same position with the Springfield (Ohio) Cardinals. As noted in the record at the left, Alston eventually worked his way up through seven teams and four levels of minor league competition; Portsmouth and Springfield (class C); Trenton and Nashua (class B); Pueblo (class A); and St. Paul and Montreal (both AAA teams).

Walter Alston was unknown to the national media, when the Brooklyn Dodgers general manager, Walter O’Malley hired "Smokey" as the Dodgers’ field manager in November, 1953.

A widespread reaction to Alston’s hiring was to ask, “Who’s He?,” as noted in the following article - which was taken from the Walter O”Malley website.

"While he explored all options off the field, O’Malley’s Dodgers enjoyed success on the field. In 1951, the Dodgers had lost the National League Pennant in devastating fashion to the New York Giants and and Bobby Thomson’s legendary “Shot Heard ‘Round the World.” In 1952 and 1953, the Dodgers won the N.L. Pennants but lost to the Yankees twice more in the World Series.

Following the 1953 season, O’Malley rebuked Manager Charlie Dressen for seeking a multi-year contract and turned to a relatively unknown baseball man, Walter Alston. The “Quiet Man” from Darrtown, OH, who played in one major league game, became Dodger Manager amongst blaring headlines “Walter Who?”

However, Alston had been a successful organizational manager, piloting St. Paul (MN) to the American Association Pennant in 1948 and the Montreal Royals to the “Little World Series” title against the New York Yankees’ Kansas City club in 1953. He signed the first of 23 consecutive one-year contracts in a gentleman’s agreement with O’Malley.”

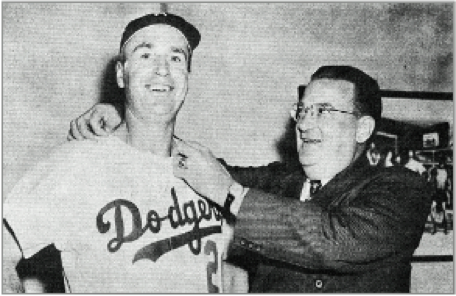

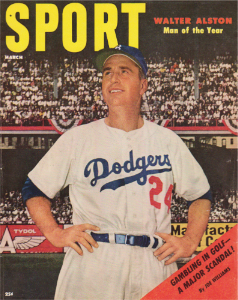

Walter Alston - Brooklyn Manager with Dodger G.M., Walter O'Malley

Image from 1955 Sport Magazine

Contributed by Paul "Pete" Jewell

The following summary of Walter Alston's entire managerial career was taken from the baseballreference.com website.

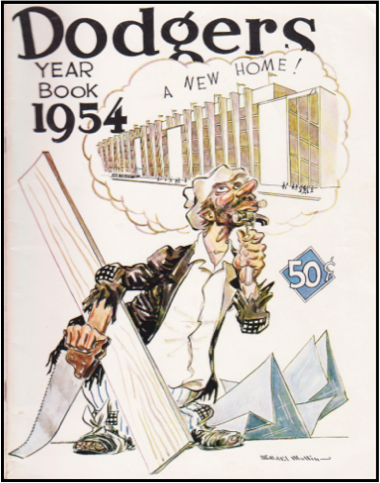

Dodgers ownership dreaming of new home

When the 1954 season began, manager Walter Alston was likely dreaming of success on the Brooklyn baseball diamond at Ebbets Field.

However, the cover of the 1954 Dodgers year book (beow left) portrayed the dream of the Dodgers ownership; a new home! Thinking that a new diamond might be possible in Brooklyn, the general public (especially, the natives of Brooklyn) likely did not envision that their beloved "Bums" would soon move to Los Angeles, California.

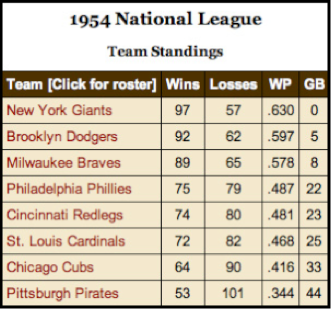

1954

In his first year as a major league manager (1954), Walter Alston led the Brooklyn Dodgers to a second place finish - five games behind the New York Giants.

In May 2009, Paul "Pete" Jewell contributed the image of the 1954 Dodger Year Book.

1955

For Brooklyn Dodger fans, the 1955 season was one to remember. The "Flatbush Bums" truly reached stardom by winning their first ten games and went 22-2. As reported in the following Sports Illustrated article, by mid-season Smokey's boys had a 12 game lead.

Dodgers start season with a flourish!

In May 2009, Paul "Pete" Jewell contributed the image of the 1955 Dodger Year Book.

SPORTS ILLUSTRATED INTERVIEW OF WALTER ALSTON

~ July 11, 1955 ~ Joan Flynn Dreyspool

"Subject: Walter Alston

Says the Dodgers' manager: 'I could go out there and raise hell with the umpire and jump up and down - but, I don't think I will'

'They've got me pictured as a quiet and dead kind of a guy,' Walter Alston said, not complaining but just stating a fact. 'Everybody seems to think I'm pretty easygoing and I probably am. Last year I think I hated to lose as badly as anybody, but I had the feeling that I did the very best that I knew how and the very best that I could do. I didn't have any guilt-consciousness that I shoulda done this or I shoulda done that.'

'I always heard the fans here in Brooklyn were really tough, but when the season was over, I felt they were even better to me than they might be. I've had no second-guessing or interference from the front office on the ball field. That's very good. It's only natural to want people on your side, but you've got to expect some for you and some against you, especially when you're in this business. You may look real bad one day, and the next day you come out looking like champions.'

In the middle of the 1955 season, Sports Illustrated magazine published a story about Walter Alston - whose managerial style had the Dodgers ahead of the rest of the National League by a dozen games.

The Walter Alston interview by Joan Flynn Dreyspool of Sports Illustrated (reprinted below) was excerpted from the Sport Illustrated Vault (a website that provides archived material). The SI Vault can be found by Googling "Sport Illustrated Vault" or by clicking Sports Illustrated Vault.

1955 - Alston Leads Dodgers to FIRST World Championship!

In his second year as manager of the Brooklyn Dodgers, Walter Alston proved that Walter O’Malley was correct in choosing the Darrtown native as the Dodgers’ field manager. Alston led the Dodgers to their FIRST-EVER World Championship, as noted in the following article - which was taken from the Walter O”Malley website.

“Meanwhile, in 1955, the Dodgers jumped out of the starting gate with 10 straight victories, went 22-2 and never looked back.

Second-year Manager Alston led the Dodgers to their first and only World Championship in Brooklyn, as they defeated their old nemesis, the Yankees in seven games.

On October 4, 1955, as the Dodgers and Johnny Podres won 2-0, the old adage of “Wait ‘Til Next Year” could be retired once and for all, as the Borough of Brooklyn overcame its second-class citizen complex and glowed in the spotlight.”

To see a summary of the 1955 World Series, visit the following link sponsored by the Baseball Almanac: http://www.baseball-almanac.com/ws/yr1955ws.shtml

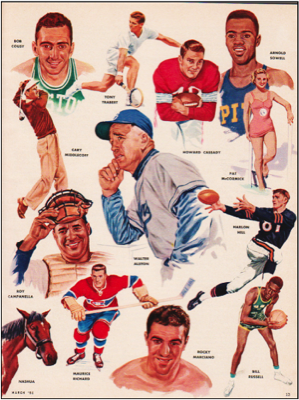

Sport Magazine Recognizes Walter Alston as the 1955 "Man of the Year"

After the Brooklyn Dodgers won the 1955 World Series, Sport Magazine recognized Walter Alston as the "Man of the Year." A reprint of the article appears beneath the three images.

Others who were considered for the award in 1955 included such sports notables as Bob Cousy, Tony Trabert, Roy Campanella, Maurice Richard, Rocky Marciano, and Bill Russell.

The three images (clockwise from the right) depict the magazine cover, the editorial that provided the rationale for selecting Walter Alston, and a pictorial tribute to all who were considered for the award.

The following is a reprint of the March 1955

Sport magazine "Man of the Year" article (pg. 15) that is cited above/right.

"When Walter Alston was given Chuck Dressen’s job as manager of the star-studded Brooklyn Dodgers, the reaction - among baseball people and newspapermen as well as the general public - was “Who’s he?” Hardly anybody had ever heard of him. It was a particular shock because Alston, a quiet man who had been laboring quietly as manager of the Montreal Royals, Brooklyn’s farm club in the International League, was succeeding one of the noisiest and most colorful managers in the business. Nor did it help, in the eyes of those who saw fit to second-guess and criticize owner Walter O’Malley’s choice, that Alston’s major-league record consisted, in total, of one time at bat for the St. Louis Cardinals. The jokesters made much of the fact that, in that one time, Alston struck out.

It is undeniably true that the Dodgers have been managed by men who were more famous, more colorful and more talkative. But none of Alston’s predecessors - not Wilbert Robinson, not Max Carey, not Casey Stengel, not Burleigh Grimes, not Leo Durocher, and not Chuck Dressen - had ever been able to give Brooklyn’s lusty fans the world championship they craved. Pennants, yes. The Brooks won National League pennants in 1916, 1920, 1941, 1947, 1949, 1952, and 1953. But, seven times they went against the champions of the American League - twice against the Cleveland Indians and five times against the New York Yankees - and every time they lost.

In 1955, Walter Alston, in his second year as field boss of the Dodgers, got his club away to the fastest start in baseball history, won the National League pennant hands down, then beat the hated Yankees in a breathtaking seven-game World Series. The man nobody had heard of had done what the glittering names of the past had been unable to do. The Dauntless Dodgers were champions of the world - the whole world, even including Japan, where the crestfallen Yankees went to revive their shattered confidence - and Brooklyn hasn’t been able to get over it yet.

Alston’s most devoted admirers do not minimize the king-sized contributions to the attainment of the world championship made by Roy Campanella, Duke Snider, Don Newsome, Gil Hodges, Jackie Robinson, Pee Wee Reese, Carl Furillo, Johnny Podres and the other Brooklyn idols. Walter did not throw a pitch or hit a ball all year. But he made a team out of the Dodgers and he made mince-meat out of the theory that the great Stengel would think him all the way back to Darrtown, Ohio, in the World Series. Furthermore, he did it the hard way, coming back from a two-down deficit to pull his team through three straight at Ebbets Field, refusing to panic when the Yankees tied it up, and wrapping up the big seventh game where every true Dodger fan would have wrapped it up - on the sacred turf of Yankee Stadium itself. Walter Alston, the man nobody knew, is the symbol of Brooklyn’s victory, the greatest achievement of the sports year. He is by all odds the Man of the Year."

1955 - "Smokey" Alston back home in Darrtown

Shares thoughts with fans and friends

In the fall of 1955, after leading the Brooklyn Dodgers to their first-ever World Series Championship, Walter "Smokey" Alston came home to Darrtown - just like he would after every season during his 23 year career as the Dodgers field manager.

This particular year, honoring the wishes and requests of his Darrtown fans and friends, "Smokey" shared his memories of that eventful season by speaking to those assembled in the Darrtown Knights of Pythias Hall.

The image at the right, contributed by Paul and Janet (Baumann) Jewell captures a moment during Smokey's address to the audience.

We can identify two others in this photograph. The young boy seated on the stage of the hall behind Smokey is Donnie Thomas. Seated beside Donnie, in the dark dress is Olive (McVicker) Hansel.

The woman whose face is framed by the left window resembles Dorrie (McVicker) Thome - although we are not positive.

Winchester Recognizes Walter Alston as the 1955 "Outdoorsman of the Year"

(The following item appeared in a 1955 Sports Magazine column. This item was contributed by Paul "Pete" Jewell - May, 2009)

SPORTalk ~ By Irv Goodman ~ Sport Magazine - 1955 - page 8

"Walter Alston, our cover boy this month, is one of the least known public figures among major-league managers - or he was until after the World Series. All anyone knew about him was that he was a career manager and he had some minor hobbies. Walt does have two hobbies - and neither is minor. He is an accomplished woodworker and an expert outdoorsman. In fact, Winchester, the gun company, has named him its outdoorsman of the year, the award carrying with it a framed sheepskin plaque and a pigeon-grade Winchester Model 50 shotgun.

The aware is non-competitive. It does not mean Alston is necessarily the best outdoorsman in America, but it does mean that he is certainly top-notch at it. He is an accomplished and experienced hunter.

The Winchester award, the purpose of which is to increase public appreciation for hunting, shooting, and the other outdoor sports, is only two years old. The first winner was Robert Taylor, the movie star. And if you’re surprised at that selection, you have nothing on John Olin, chairman of the board of Olin Mathieson, parent firm of Winchester. Olin is one of the country’s best-known hunters. Like many of us, he had heard that actor Taylor was an expert shot, and excellent fisherman, a fine horseman, and an accomplished dog trainer. But, Olin and his colleagues wanted to be sure Taylor was as good as he was said to be. The best way to find out, they decided, was to invite him on a hunting trip, and have some Winchester experts judge him. So Taylor and his wife, Ursula Theiss, went out for three days of duck and pheasant hunting. Shooting from some tough duck blinds, Taylor had to do some “pass-shooting” - that is, firing at ducks traveling at top speed at an altitude of some 40 yards.

Walter Alston in the field, with friend and Darrtown resident, Howard Cox.

The first morning, hunting with dogs for pheasant, Taylor took five shots at the flying birds. He bagged five birds. That afternoon, he went into the duck blinds. Two hours later, he had fired six shells for an unbelievable bag of six ducks. The unanimous consensus of the crew of experts was that Taylor was one of the finest wing shots they had ever seen anywhere, any time. The award was settled.

Alston, who had been shooting and hunting all his live, did not have to submit to any such testing. The Winchester people knew that Walt was good. In fact, they apparently have more regard for his talents that some of his baseball critics used to have."

1957

Late 1957: Dodgers Leave Brooklyn for Los Angeles!

The baseball Dodgers belonged to Brooklyn for 67 years (1890 to 1957). Then the team moved to Los Angeles. Numerous websites lament Brooklyn's loss. One perspective is offered at: "O'Malley vs. Moses"

1963

Los Angeles Dodgers over New York Yankees (4-0)

The Los Angeles Dodgers swept the New York Yankees four games to none in the 1963 baseball World Series. More info is available at: https://www.baseball-almanac.com/ws/yr1963ws.shtml

Darrtown Memories of the 1963 Los Angeles Dodgers

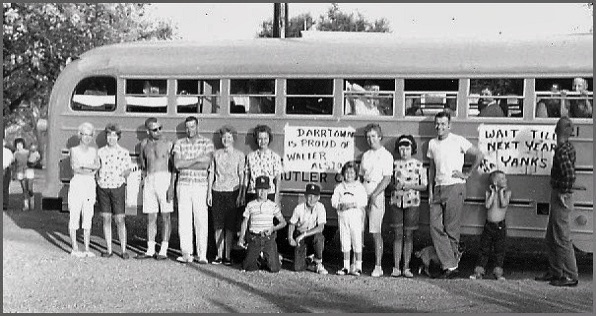

After the Dodgers swept the New York Yankees in four games (holding the "Bronx Bombers" to a total of four runs in those four games), Darrtown celebrated with a parade, shown in part with the following three images, which were contributed by Jack and Betty (Lindley) Daniels.

In the image above, the parade assembles on Scott Road, east of Darrtown - across the road from the Lawrence Bauman home. The car at the left was a Butler County Sheriff patrol car; the fire truck belonged to the Milford Township Fire Department.

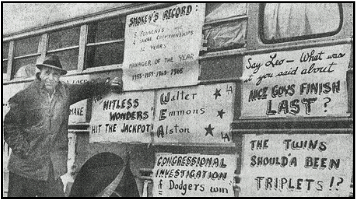

The former school bus shown above, in the Hitching Post parking lot, was used, on this parade day, to transport fans and display congratulatory signs. The co-owners of the bus (Jack Daniels and Fred Lindley) were in the process of converting it to a family camper.

In the photo at the right, the man wearing a white tee-shirt is Harry Ogle, son-in-law of Walter Alston.

The girl standing to our left of Harry is Donna Jo Amiot.

Next left is Dodie Ogle, Harry's wife and Smokey's daughter.

Left of Dodie is Kim Ogle (standing) and Rob Ogle (kneeling) - grandchildren of Walter Alston

1965

Los Angeles Dodgers defeat Minnesota Twins 4-3

The Los Angeles Dodgers defeated the Minnesota Twins four games to three in the 1965 baseball World Series. More info is available at: https://www.baseball-almanac.com/ws/yr1965ws.shtml

The Dodgers defeated the Minnesota Twins in seven games and on October 24, 1965, Darrtown-area fans of Walter Alston once again celebrated with a parade - shown in part with the following images - which were taken from newspaper clippings contributed by Jack and Betty (Lindley) Daniels.

The 1965 parade photo at the right (top) shows Walter and Lela Alston and grandson, Rob Ogle and granddaughter, Kim Ogle.

Walter Alston appears in the front passenger seat (Gary Dillon is the driver, according to the the Cincinnati Enquirer news article below). Seated in the rear (left to right) are Rob, Lela, and Kim.

The photo at the right (bottom) shows Walter Alston beside a camper bus, adorned with congratulatory signs. This image appeared in the October 25, 1965 edition of the Cincinnati Enquirer. It was found in a scrapbook that was maintained by Mrs. Albert (Bernice Weiss) Lindley.

Gilson Wright, Oxford Press correspondent to the Cincinnati Enquirer wrote the story (below) that accompanied the photo.

Darrtown Hails "Smokey" Alston, Her No. 1 Son

The Cincinnati Enquirer / Miami Valley / Butler-Warren News ~ By Gilson Wright, Enquirer Correspondent ~ October 25, 1965

DARRTOWN - "It was “Welcome Smokey” Day in this Butler County village Sunday for Walter Alston, manager of the Los Angeles Dodgers.

Darrtown’s No. 1 citizen and the town’s biggest booster had arrived home last Friday. His fellow citizens organized a parade over the weekend and the motorcade of about 50 automobiles was given a deputy sheriff’s escort to Oxford and back Sunday afternoon.

The Dodger manager and Lela, his wife, as well as their two grandchildren, Rob, 12 and Kim, eight, rode in 40 degree weather, on the eight mile round trip in a convertible driven by Gary Dillon.

With sirens screaming and the bells of the Milford Township fire engine ringing, the parade brought people by the hundreds form their homes and from the residence halls of Miami University, where the celebrated Dodger leader played his college baseball 30 years ago. He was also a varsity basketball regular.

The new convertible was a far cry from the model-T Ford Alston used to drive from home to his classes on the campus in those depression years when a 0 loan from a Methodist preacher helped him squeeze his way to a diploma.

Alston was in high spirits and deeply appreciative of the enthusiasm which his fellow townspeople, friend of many years, showed.

Asked by a photographer to pose in a stiff wind alongside a school bus bearing a lot of signs, Alston said that the heavy jacket he was wearing “isn’t good advertising for Darrtown’s weather.”

“It’s better than that Los Angeles smog,” the photographer quipped.

All the Alston family took part in the parade. Beside his wife and grandchildren, there were his daughter and her husband, Mr. and Mrs. Harry Ogle; his parents, Mr. and Mrs. Emmons Alston; Mrs. Alston’s mother, Mrs. Grace Alexander, and brother-in-law, Clifford Alexander, and his wife. Alexander serves as a scout for the Dodgers, but spends the off season as a teacher.

Alston always comes home as soon after the season as possible. He will relax here until spring training starts."

MANAGING CAREER - major leagus

PLAYING CAREER

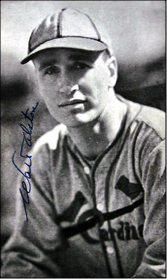

Walter Alston

Rookie card

1974

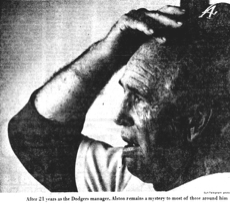

Sports column depicts Walter Alston as "The Man Nobody Knows"

THE MAN NOBODY KNOWS

San Bernardino Sun, 21 July 1974

By BETTY CUNIBERTI - Sun-Telegram Sports Writer

LOS ANGELES - It is 4:30 p.m. in Los Angeles, and the baseball game will not start for three hours. Yet, the Dodgers are erupting with activity. Tommy Lasorda, the Dodgers third base coach, is conversing in fluent Spanish with three of Manny Mota's boys in the dugout. Lasorda, a paunchy Italian generously endowed with vocal cords, wants to know which Dodgers are ugly.

"Willie Crawford es feo?" asks Lasorda.

"No!" reply the children.

Manuel Rafael Mota, age four, crawls up in Lasorda's lap and sucks his thumb contentedly.

Tom Paciorek, one of the more talented bench-sitters in the league, is not half as content as little Manuel. He spots a woman reporter in the dugout sitting beneath the lineup card and he decides to let off steam.

"Why don't they put her name on the list?" asks Paciorek, taking a seat next to Lasorda. "She's probably more important to this ballclub than I am!"

Paciorek tells Lasorda an X-rated anecdote (the children know little English) and hugs him around the neck in laughter.

On the field, the Dodgers' ace reliever, Mike Marshall, is instructing seldom used Geoff Zahn on the intricacies of covering first base. They've been at it since 4 p.m.

A 62-year-old man walks through the dugout, and no one seems to notice. No one asks if he is ugly. No one asks him about the lineup card. No one asks him for tips on covering first.

The man is Walter Emmons Alston, and he runs this show, although he appears more to be watching it.

When Alston was hired to manage the Brooklyn Dodgers in the fall of 1953, a headline in an eastern newspaper read, "ALSTON (WHO'S HE) TO MANAGE DODGERS." Twenty-one years, six pennants, and four World Series championships later, many still ask the queston, "Alston, who's he?"

The name is familiar but the man behind it is a mystery.

He Is quiet and unassuming, almost to the point of obscurity. He is cool, but never curt. His door is open, but there's not much traffic. He is obliging to the press, but seldom quotable.

In a word, distant. Or, in another, successful.

He's the strong, silent type of hero, if he is a hero at all.

Only two men have managed one ball club for more than 21 years Connie Mack (Philadelphia Athletics, 1901-1950) and John McGraw (New York Giants, 1902-1932). Indeed, Alston's most heroic quality may be endurance of years - and of criticism.

There were lean Alston years such as 1958, when the club moved to Los Angeles and finished seventh; 1962, when the Dodgers blew their first-place lead and lost the pennant to the Giants in a playoff; and 1964, when the Dodgers finished sixth. Yet, each of those bad years was immediately followed by a World Series championship 1959, 1963, and 1965. Alston at times has been under heavy fire from both players and press in regards to his way of communicating, or, if you will, not communicating. He admits that his assistant coaches do much of the man-to-man instruction, but he prefers it that way. And It is difficult to knock its apparent success.

The Dodgers lead the National League West by 6 1/2 games, and finished in the top three the last four years. Alston has signed 21 one-year contracts to do a job in which the average tenure is 2 1/2 years.

Above all, he has earned respect. His appearance in the dugout or the dressing room immediately brings about the atmosphere of a Church Reverence. The Dodgers' dressing room has been called the most placid in baseball, a barren desert for a reporter looking for a refreshing quote.

But that is Alston's way. He is, as the players call him, the Skipper. An imposing figure, at 6 foot 3, 220 pounds, Alston's white hair and wrinkled, freckled face give a strange aura of awe. When you meet him, you feel as if you should genuflect, or at least, drop an offering In the collection box.

Alston enjoys the respect he draws, but he would rather have been revered as a great ballplayer.

Contrary to what most people believe, Alston was a ball player: He just wasn't a very good one. He played a couple of months for the St. Louis Cardinals in 1936 and struck out his only time at bat.

"Yes, if I'd had my druthers, I would rather have been a ballplayer," said Alston. "I may not have stayed around as long, I guess.

"I would rather have been a good one, not a mediocre one."

Instead, he went on to become baseball's senior manager. He tried to avoid telling people why he has stayed in the business so long, saying simply that he enjoys it. With some prodding, he finally says, "Honestly, down deep - I try to keep it to myself - but, down inside I feel I can do the damn job better than anybody I know. '

"I don't consider myself a boastful individual. I guess it's cockiness in a way, but I feel I could beat you at marbles or tiddlywinks or anything else."

Alston finds reward In doing the best job possible.

"I guess I've stayed around because of that feeling of when you win, everybody's happy and popping off. Also the times when we lose and everybody's quiet.”

“If, at the end of the season, I don't have a guilty conscience, if I do my best every game and get the players to do their best, then I can sleep well. That's my philosophy.”

"I would like to win a lot more pennants. I’m getting anxious. But, if I do the best I can, the standings will take care of themselves. It's silly to worry about everything."

Alston credits his longevity as a manager to the Dodgers organization.

"Ninety-nine per cent of it is that I've been fortunate enough to work for a good organization," said Alston. "The organization has supplied me with good ball players. I'm sure the players make the manager, aren't you?"

Alston never seriously considered quitting, although he plans to retire in the next five years.

"No, I never really thought of quitting," said Alston. "I think I like what I'm doing, you have to put up with the aggravation."

"In spite of all my hobbies and things, I suppose when the grass got green in spring, I'd be wishing I were in spring training.”

"I don't have any goals. I haven't set any time when I'll retire. Within the next five years? That's plenty. I'm not saying I'll be around that long."

Alston was born the son of a sharecropper on a farm in Darrtown, Ohio. He began courting his wife, Lela, when he was a junior and she was a sophomore at (the) Township High School. Alston attended Miami of Ohio University, where he flunked English his freshman year.

"It was tough for me my freshman year," said Alston. "English Literature and all that stuff didn't appeal to me, I didn't care what Shakespeare and Chaucer and those guys did."

He dropped out of college after his freshman year and married Lela. Although not a religious man, Alston was persuaded to go bark to college by a Reverend Ralph Jones, who gave him $50 and told him to get back in school.

"I think, really, I just went back to school so that I could play baseball somewhere where some scouts would see me," said Alston. "My junior and senior years, I had A's and B's and came close to being on Ihe honor roll."

Alston was also the captain of the basketball team, and played in one game against a forward named John Wooden.

"I didn't even know it until two years ago," said Alston. "Wooden's team won, but I don't remember the score."

After he graduated, Alston discarded his childhood ambitions of being a farmer to become a part-time teacher, ballplayer, and manager. Alston taught a variety of subjects (not English) at two Ohio high schools for 14 years.

"They got sick of me teaching five months a year," said Alston. "So I quit and managed full time."

Alston managed the Dodgers' St. Paul AAA club for two years and then led the Montreal AAA club for four years.

The next move was to Brooklyn. And the next to Los Angeles.

Today, Los Angeles is still only a part-time residence, a home away from Darrtown.

Alston and his wife live in a hotel-apartment in Los Feliz, a few minutes' drive from the ballpark.

At Dodger Stadium, Alston manages his way, the quiet, country way.

Oddly, Alston said that if he had one thing to change about himself, he would like to he more outgoing.

"I suppose I may be a little tough for strangers to make friends with," said Alston, puffing one of a chain of cigarettes. "I could be a lot more I don't know what the word is. I'm friendly, but I don't get too close to anybody. Except my friends, of course. I get close to the coaches."

Alston plays golf with Dodgers coaches Jim Gilliam, Monty Basgall, and even the clubhouse man, Nobe Kawano. He would like to have comparable relationships with his players, but finds he is unable to.

"The better you know your individual players, the better you do. I'd like to play golf with all of them, but there's no way I could do it," said Alston, not particularly enjoying the question. "I don't chum around with my players, because there's no way to chum around with all 25. I don't think it would be good to get close to a few.”

"I try to be friendly. I leave my door open, but I have to stay a certain distance."

Alston is not one to display anger, or any other emotion, in public.

"I don't like to pop off," said Alston. "I would differ from a manager like Leo Durocher who raises a lot of hell. Some managers have better success that way, but I can't copy them. If I tried to copy Durocher, I wouldn't be as successful as doing it my own way. And I wouldn't expect anyone to copy my way of managing. It's all in your own personality."

"In a team meeting, I have their attention. I get my point across." Alston's favorite form of communication with the players is the quick joke, the tease - something he calls "agitate."

"I do like to agitate once In a while," said Alston. "I think that kind of a relationship is great."

Alston prefers brief conversations with his players and normally Ihe exchange must begin at the other end.

Communication flows more freely between the players and coaches, Red Adams, Basgall, Gilliam, and Lasorda. The assistants do perhaps more than the normal amount of instruction and counseling, and often they receive credit for the Dodgers’ success.

Alston has managed each of his 21 teams differently, according to its abilities.

"In Brooklyn, we had a bunch of power hitters and a small park. We didn't do much bunting, or hit and run. Then we got the speed of Maury Wilis and the good pitching of Don Drysdale and we went with that kind of game," said Alston.

"You have to adjust to your own team. Twenty-four of them, you encourage, talk to them, and brag on them 99 per cent of the time. The rest of the time you kick them in the pants.”

"I treat everybody equal. At the same time I know , which players to pat on the back once in a while. The young players need more encouragement."

Alston, a grandfather of two teenagers, will be eligible for Social Security benefits in three years. He finds himself in the precarious position of managing one of baseball's youngest teams. His newest player, pitcher Rex Hudson, was born the year Alston became the Dodgers manager.

The locker rooms in Brooklyn smelled like old socks and chewing tobacco. Today, there's an odor of Brut in the air, and Alston's jokes barely can be heard above the whirr of hairdryers.

But beneath the perfume and body shirts, Alston says the players are pretty much the same.

"I think young players have the same excuses, the same problems, and the same alibis, as they've had for the past 99 years," said Alston, dismissing the possibility of a generation gap. "They may talk a little bigger, but that's about it.”

“The older ballplayer had to work harder to get through the minor leagues and he appreciated it more. Now, they sign for a big bonus and have cushions on their benches. Maybe the young players don't appreciate the luxuries as much.”

Alston himself still appears to be more awed by the luxuries than appreciative of them. Despite his big-city fame, he is still a country man at heart. During the offseason, he returns to Darrtown and lives in the same house with his daughter's family, across the street from where Alston's father lives in a house Alston helped build.

Alston's salary is estimated at $85,000 a year, but his needs could be satisfied by a minor leaguer’s earnings.

"I just need enough money to eat well, take care of my family, have a good horse, a shotgun and a couple motorcycles," said Alston. "Baseball's been good to me, and I wouldn't change anything that's happened. Back home, we just had enough to eat and we worked our fannies off from daylight until dark. When you don't know any different you don't learn to expect too much."

Although Alston is easily the most successful of his childhood pals, the people in Darrtown haven't noticed. "I get asked for autographs in New York or Los Angeles, but back home I'm just one of the gang, one of the farmer boys. That's the way I want it," said Alston. "I suppose they look at me as just a good neighbor. I haven't won that many pennants that I can go changing, but I wouldn't change if I'd won them all."

Alston's pleasures are simple ones. On the road, he stays in his room most of the time, watching TV or reading. "I read baseball magazines," said Alston. "And I read some of those pickup, paperback books. Some of those books are sexy, but that's all right, isn't it?”

"I used to be a great movie-goer, but now I think TV has taken over. I like detective shows, and of course cowboy shows."

When he can't be In Ohio riding horses and hunting rabbits, Alston Is content with shooting skeet somewhere between freeways.

"I do a lot of skeet shooting. Do you know what that is?" said Alston. "Out here I go down the Pomona Freeway to the International Gun Club. It's a place where you can forget your troubles. It's better than sitting in the apartment, worrying about tonight's game."

Alston's pride and joy is his pool room, where he wins a majority of contests against family members. After pool, the family, Alston's wife, his daughter, Doris, and her husband, Harry Ogle, sit down for a game of bridge.

"We have to change partners," said Alston. "I agitate my daughter and my wife until they get distracted." Alston rides motorcycles with his grandson, develops film in his own dark room, and is an expert woodcarver. He plays golf and shoots "anywhere from 80 to 100. I have more trouble with direction than distance," said Alston.

His taste In food?

"The old farm kind," Alston says heartily. A wide grin reveals large teeth, slightly yellowed with age. "I like meat and potatoes, steak and potatoes. Ice cream. I like ice cream. We make our own back home. I made the machine that makes ice cream, that's enough, isn't it?" '

His taste in women?

Another deep grin appears. He puffs on his cigarette and smiles again. He puffs again. "Are you sure you should print this?' he asks.

"I think good looks, intelligence, affection. . .you know."

An honest, uncomplicated man going on 63 years old, Alston is one of a kind. He will be remembered perhaps not as a great manager, but surely as a good man who did the best he could for many years.

"I don't worry about getting old. It's something everyone has to face," said Alston. "I don't know what I'll do. I guess I'll do more of the things I do at home, play more golf. I might like to scout part-time.”

"I would just like to be remembered as a good manager, and most of all, a good guy along with it. Nothing special.”

========================

QUOTES ABOUT ALSTON:

“My opinion of him hasn't changed. For the first five years his players made him. Since then, he's helped make some damn fine players.” - GENE MAUCH

"He has a great ability to remain consistent. That adds to the stability of the ball club." - RON FAIRLY.

"I played for him for many years and I was happy while I did. He has had an illustrious career and I wish him well." - WILLIE DAVIS.

"His most outstanding attribute is that he remains cool. I've seen him get mad, but only three or four times in all the years I've known him. That's not very many." - DUKE SNIDER

"He treats everybody the same, like a man. He's the kind of guy you can go in and talk to anytime you want." - JIM GILLIAM.

"I took a problem to him once. Never again. I was unhappy about something and he said something like, 'Tough luck.' Ballplayers are people and they like to know , WHY something is happening, but he never talks to us." - BILL BUCKNER.

"I've always wanted to play for Walter Alston." - JIMMY WYNN.

"He's mellowed In the 10 years I've played for him, but he still demands 100 per cent from everybody. He has the respect of his players and he knows his baseball." - WILLIE CRAWFORD.

"He's the captain of the ship. He knows what each player can do and gets the most out of him. The players respect him and it was a thrill for me to play for him." - RON HUNT.

========================

URL to the original newspaper article: https://cdnc.ucr.edu/cgi-bin/cdnc?a=d&d=SBS19740721.1.39&e=-------en--20--1--txt-txIN-darrtown-------1

The Baseball Almanac website describes the event in the following manner: “Alston was 24 years old when he broke into the big leagues on September 27, 1936, with the St. Louis Cardinals.”

Click to see: