‘The cart was always full of baseball bats and balls,’ he said.

By the way, writers who give Hamilton, as his place of birth, are technically correct. The address was served by the Hamilton post office. But, Walter was born in a long-gone cottage near Venice in Butler County, former site of the always well-attended annual Scribes Picnic, public festival which had its heyday in the ‘twenties.

He was born on December 1, 1911, seven months to the day after the writer of ‘My Land!’ But, when Walter E. was only a couple of weeks old, Emmons and Mrs. Alston took him to Preble County to live. They made their home, on a farm, between Camden and Morning Sun for several years, finally moving to Darrtown, presently the Alston address (4340 Cherry St. at the intersection of Apple St.).

Smokey played Miami University varsity baseball, of course, and for several years played Sunday ball in the Clark-Butler County League, as the writer well knows. ‘My Land!’ still has knobby bones in his left hand from tosses the six-foot shortstop flipped at it, between innings, when ‘My Land!’ was an alleged second baseman.

We played with the Oxford Merchants, Baldwin’s Grocery and Riley and Riley Grocery teams, winning most of our games in the mid-thirties and sending Smokey and a few others up for big-league tryouts. Smoke was the only one who ever made it into the top category.

Some names you may know are Stan Lewis, Jimmy Boyd, Len Fertig, Hoot Fowler, Phil Morrical, Cliff Alexander, Charles Ross, and Ty Powers. Cliff made it to the Dodgers and to the Reds as a superior scout. He and several others had some professional baseball experience.

It wasn’t unusual in those days for 500 fans to come to Hamilton, from Oxford, to watch us play, the contingent usually headed up by irrepressible Roger Beal, who believed the aggregations collected by Merle (Cairo) Sheard and Jim Clark could not lose. He was almost right - we lost very few games, as Journal News files can show you.

After those days, ‘liver ball’ came into its own and hardball gave way to it."

But, back to Smokey. There’s about as much chance of him getting out of baseball as there is of Pete Rose walking to first base. Once a Dodger, always a Dodger…"

Biography - Walter Emmons "Smokey" Alston

RETIREMENT

September 29, 1976: Walter Alston Retires as Manager of the Los Angeles Dodgers

When Walter Alston retired as manager of the Los Angeles Dodgers, Pete Chappars wrote the following op-ed piece in the Oxford Press. The photo that appears below accompanied the September 29, 1976 news article.

"Outer-Oxfordites 'Remember When' Smokey Ponied Up

By Peter Steve Chappars / author of 'My Land!' column ~ September 29, 1976

OXFORD - "Oxford-area and outer-Oxford places - Morning Sun, Reily, Venice (Ross), and Darrtown - are buzzing with news that Smokey has given up the steering wheel of the Los Angeles Dodgers National League baseball team.

People are “Remembering When” and recalling Walter Emmons Alston as a boy, as a young man, as a ballplayer and student as a pool player, hunter, and trap shooter.

Harvey Bell, Farmersville, who works at Withrow Court, Miami University campus, where Smokey played a lot of basketball, Tuesday, said he remembers when the big man was a small boy, driving a pony to school, in Morning Sun.

Esteemed sports columnist Jim Murray acknowledges the retirement of Walter Alston

IMMEDIATELY BELOW is a reprint of a column that appeared at the top of page 22 in the Hamilton (Ohio) Journal-News on Friday, October 8, 1976 in which Los Angeles Times sports writer, Jim Murray addressed the retirement of Walter "Smokey" Alston as the manager of the Los Angeles Dodgers.

To fully appreciate the significance of the sentiment expressed by the Pulitzer Prize winning writer in writing a "fond farewell" to Smokey Alston, one needs to know the style in which Jim Murray typically wrote. The following links provide a background of Jim Murray's writing and his impact on sports journalism.

From the Los Angeles Times: "Jim Murray, Pulitzer-Winning Times Columnist Dies"

From the Tucson Weekly: "The Legendary Sportswriter Made This Kid Want To Write"

From the New York Times: "Jim Murray, 78, Sportwriter And Winner of Pulitzer Prize"

From the just-one-liners website: See quotations from author, Jim Murray

REPRINT OF

JIM MURRAY'S RESPONSE TO WALTER ALSTON'S RETIREMENT

Columnist's fond farewell is notable for its praise of Walt

***********************

"All right, Miss Tulsa, put away those poison pen letters for a minute and take a letter to Walt Alston. Send it care of the Dodgers. I don’t think Darrtown has a post office yet. Mark it “Urgent” and sign it “Affectionately.”

"Dear Walt,

See I told you it wouldn’t last. That O’Malley is a fickle character who changes skippers on a whim every 23 years.

I’m going to miss our little chats on the infield fly rule and the balk motion. I was just beginning to get the hang of it. I don’t think we ever once discussed anything that didn’t go on between those white lines out there. I don’t know whether you’re Republican or Democrat or Catholic or Protestant and I’ve known you for 18 years. I never heard you tell a lie, saw you take a drink or talk about anyone behind his back. I heard three generations of your players cut you up - usually after their third martini or while trying to impress the lady on the next bar stool.

I’ll never forget the time on the team bus a bunch of guys were discussing some bistros in New York and you said with a perfectly straight face, ‘What do people do in night clubs?’ They looked at each other for a moment but, when the answer came that they sit there and drink, you shook your head and said, ‘They could do that in their room - at no cover charge.’

I know you didn’t spend all your life making fudge and bobbing for apples - you could cuss like a ferryboat captain - but if you had any major hang-ups, I never saw it. You were testy with me on a few occasions, but that was before you came to appreciate the vast knowledge of baseball that I have accumulated. Let’s face it, Walt; you could never have won those pennants without me.

I’m going to miss our little jokes about Darrtown. You know. ‘We don’t have an airport; but, we have a birdbath.’ ‘Darrtown’s international airport has ducks in it.’ ‘The train only stops here, when it hits a cow.’ ‘We don’t have a street; but, the trees are blazed.’ ‘Main Street is the ploughed field, without corn in it.’ ‘We don’t have burlesque; but the widder Brown leaves her shades up.’ ‘They would have put a traffic light on Main Street; but, the cows are color blind.’ ‘An energy crisis is when your mule dies.’

I never got the impression you were afraid of a damned thing. And that went for 220-pound left fielders or the job stealers the owner use to hire, under you, to put a little Broadway in the act. Next to you, they were showed up as the petty little back-alley schemers they were. It was like a bug biting an elephant.

You were a college graduate with a teacher’s degree, but you used to say ‘extry’ all the time. You were as Middle Western as a pitchfork. Black players, who have a sure instinct for the closet bigot, recognized immediately you didn’t know what prejudice was. You were as straight as John Brown’s body. There was no ‘side’ to Walter Alston. What you saw was what you got.

But, I guess the thing I’ll always remember is that you never had to worry about what sort of ‘mood’ Walter Alston was in. You were as approachable as a hunting dog. As long as I live, I will never forget that dressing room in the playoff of 1962, when the Dodgers blew a 9th inning 4-2 lead and the pennant. The players locked themselves in and passed the bottle. You came out, dry-eyed… and dry throat and talked to us, then went over and congratulated the Giants and Alvin Dark. You had won a playoff, too, three years before.

I sat with you through 10-game losing streak in 1961 and never once saw you bust up a locker or punch a newspaperman. That’s why, when you turned on a newsman this summer, I couldn’t have been more shocked if they caught St. Francis of Assisi poisoning bread crumbs.

Your life is summed up in Jack Tobin’s biography ‘One Year At A Time.’ I don’t know of anybody leaving his profession with more respect. You took a four-straight loss in the ’66 World Series with a shrug. You had won in four straight, too, three years before. You didn’t panic, when they took your slugging team, from a bandbox in Brooklyn to the Coliseum in L.A., which was about as suitable for baseball as a deck of an aircraft carrier. You won a pennant on that aircraft carrier the second year.

I used to laugh when someone would say, ‘Why shouldn’t Alston win with all that talent?’ and I’d say, ‘Yeah. Too bad he doesn’t have some better baseball players to go with that talent. I think you ran that wild animal act that was the Dodgers about as well as it could be run, without a whip and a chair.

So, I’ll be seeing you, Walt. Give my regards to beautiful downtown Darrtown. I don’t know what time your stagecoach gets in; but, when the natives ask you where you have been for the past 23 years, tell ‘em you found seasonal work in Californy. But, don’t tell ‘em what happened to Custer.

The corner of the dugout is going to look funny without you there, next year. I only hope the Dodgers don’t, too.

Affectionately,

The Old Second Guesser”

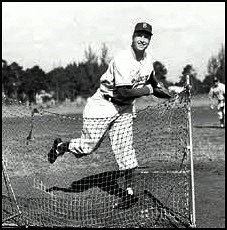

RIGHT:

Walter "Smokey" Alston throwing batting practice in spring training.

Image from walteromalley.com

Respected sports columnist Red Smith acknowledges the retirement of Walter Alston

IMMEDIATELY BELOW is a reprint of a column, written by Red Smith, that appeared in the New York Times on October 3, 1976.

To fully appreciate the significance of the sentiment expressed by the award-winning sports colunmist, please consider the credentials earned by Mr. Smith over his writing career.

From the New York Times: Walter Wellesley "Red" Smith was an American sportswriter. Smith’s journalistic career spans over five decades and his work influenced an entire generation of writers. Smith became the second sports columnist ever to win the Pulitzer Prize for distinguished commentary in 1976. Writing in 1989, sportswriter David Halberstam called Smith "the greatest sportswriter of the two eras."

QUIET MAN OF DARRTOWN

By Red Smith

"There is a new book called “A Year At A Time,” by Walter Alston, with an assist from Jack Tobin. A copy arrived in the mail recently and was opened for the first time yesterday. That was a curious accident of timing, for on Page 168 Alston says: “I've got the best job in the world.” The curious accident is that Walter doesn't have that job anymore. After working out 23 one-year contracts as manager of the Dodgers, he resigned the other day. “There comes a time,” he said, “when you get enough of everything.”

“Walter won't confirm or deny that this is his last season,” Tobin wrote in a note that accompanied the book. “I hope not, for him personally. He'd be lost without those flannels to wander around in, planes to catch and signs to flash.”

Tobin could be mistaken, and not just because the Dodgers wear double-knits instead of flannels and don't have to catch planes, because they have their own aircraft and it always waits for them. “Baseball's my business and I love it,” Alston says in the book. But he also loves his family, he loves his home in Darrtown, Ohio, he loves dogs and horses and enjoys all kinds of shooting - birds, trap and pool. A man with his inner resources is not likely to feel lost wherever he is, in the pressure‐cooker of a pennant race or the security of Darrtown.

Living Americana

Walter once described Darrtown. “When you meet a neighbor he doesn't say, ‘Hello, how are things?’ he knows how things are.” In the book he says: “Maybe, if we count the cars and the dogs and the horses, there are about 300 of us.” Yet back in the 1950's when Alston was leading the Dodgers to one championship after another, Frank Graham Jr., who was then doing public relations for the club, addressed a Christmas card to Walter E. Alston, Darrtown, Ohio. It came back stamped, “Addressee unknown.”

Walter's retirement closes the book on one of the longest and most successful careers any baseball manager has known. Not one of the most colorful, whatever that word means. Not one of the noisiest. Not one of the most turbulent. Yet it was remarkable for more reasons than one. Patience, forbearance and loyalty are adjectives seldom applied to Walter O'Malley, Alston's employer, yet the only managers who beat Alston's longevity record with one team were Connie Mack, who owned his club, and John McGraw. Only Mack, McGraw, Casey Stengel and Joe McCarthy managed more pennant winners than Alston: only Stengel, McCarthy and Mack had more world champions. All of these others are in the Hall of Fame, naturally.

Soon after he arrived in Brooklyn in 1954, somebody referred to Alston as The Quiet Man and the name stuck. Compared to a brassy egomaniac like Leo Durocher he is indeed quiet, but he is not inarticulate, he is not uncommunicative.

Get him talking about his youth and you hear a saga of rural America - Walter at 5 or 6 shagging fungoes batted by his father, with his mother taking the relay, because the kid could not throw the ball all the way in; Walter playing shortstop for the Baldwin Groceries team with his father, his uncle Stanley Alston, and uncle Paul Neanover as teammates; Walter scoring 60 points the night Milford Township High beat Jackson High at basketball, 74‐10.

In Walter's boyhood there were town baseball teams in Somerville, Seven Mile, Scipio, Collinsville, Oxford, and when Armco Steel of Middletown rang in Charley Root, then a great pitcher with the Cubs, to beat Darrtown, the folks in Darrtown raised $100 and hired Hod Eller of the Cincinnati Reds to beat Root in a return match, 2‐1.

“When I was playing manager of Springfield, Ohio,” Alston recalled one day sitting in the visitors’ dugout in Shea Stadium, “I hit a line drive over the left‐field fence in Youngstown, hit another over the wall in center and another over the wall in right, but my hardest shot of the day was a double against the fence in left. Our pitcher threw a no‐hitter, and in the paper next day my name only made the box score.”

Inward Tranquillity

He told the story with same wry, one‐sided grin he had worn on Nov. 24, 1953, in the Dodger offices at 215 Montague Street where O'Malley presented Brooklyn's new manager to the press and reporters asked about his background as a first baseman with the St. Louis Cardinals. He summed it up: “One inning against the Cubs, one putout, one error, one time at bat.” Lon Warneke struck me out.”

Usually in his dealings with people, that grin is present. Walter is the first to admit, however, that he is capable of anger. In his book he describes a shouting scene on the street in St. Paul when he challenged a big loudmouth who had been heckling him in the ballpark. In his first training camp with the Dodgers he invited Jackie Robinson to settle a disagreement man to man, and as recently as this summer he made a similar offer to a Los Angeles sportswriter who had recommended that the Dodgers fire him. Walter is 64 going on 65.

The flashes of anger are rare squalls in a summery disposition. Mostly he has gone his imperturbable way doing his job and doing it well, confident of his own judgment, bringing an inward tranquility to a scene that is almost always in turmoil.

“And now,” says a prophetic line in the book, “what I want to do, when I hang them up with the Dodgers, is just to go home to Darrtown and do the little things I enjoy so much.”

See the Red Smith article in its original context from October 3, 1976, Page 161 at:

https://www.nytimes.com/1976/10/03/archives/quiet-man-of-darrtown.html

Desert Sun

Palm Springs, CA

April 4, 1983

Alston ‘comfortable’ after heart attack, signs stable

CINCINNATI (AP)

The condition of former Los Angeles Dodger Manager Walter Alston, who suffered a heart attack Friday, was upgraded Sunday from critical to serious, a spokeswoman at Cincinnati’s Deaconess Hospital said. “His vital signs are stable, he is resting comfortably and he is alert,” the spokeswoman said.

Alston, 71, managed the Brooklyn and Los Angeles Dodgers for 23 years. He was voted into baseball’s Hall of Fame on March 10 and is due to be inducted this summer in Cooperstown, N.Y. He was hospitalized Friday after suffering a heart attack at his home in Darrtown, Ohio, about 35 miles north of Cincinnati.

The attack came shortly after Alston returned home after spending five weeks at the Dodgers’ training headquarters in Vero Beach, Fla. Alston had been scheduled to throw out the ceremonial first pitch at Friday’s opening day game at Dodger Stadium with the Montreal Expos.